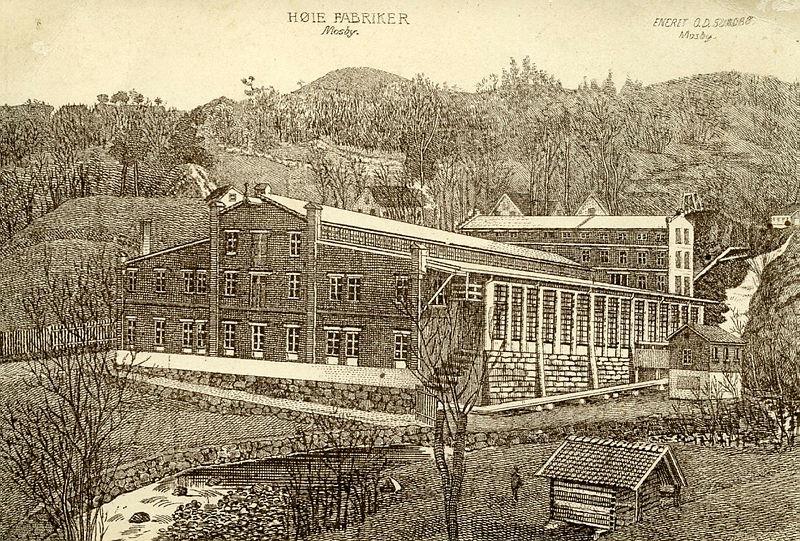

Post card featuring Høie Factories approx. 1910–1911

O. D. Sundbø, Torridal Historical Society

Post card featuring Høie Factories approx. 1910–1911

O. D. Sundbø, Torridal Historical Society

Before you lie the remnants of the lake Lona, which was dammed up to supply Høie Factories with hydropower and electricity. Høie Factories was a cornerstone industry in the emerging community in Mosby, with hydropower as a decisive precondition. The water reservoir level was lowered, and only the colour difference in the rock shows how high the water level used to be.

Below is a map showing the location of Lona in relation to Høie Factories.

The factories by Høievassdraget

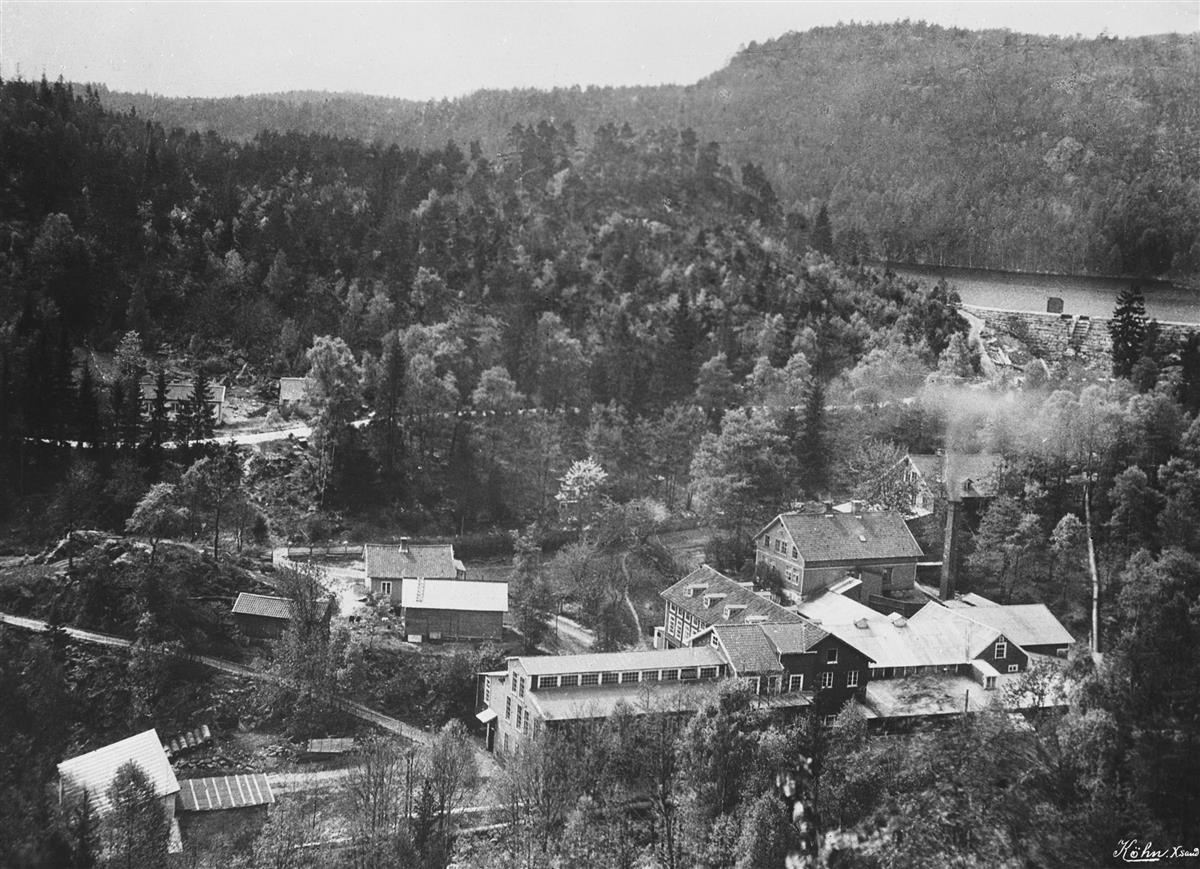

Høie Factories in Mosby in 1922. On the right in the photo is the Sagtjønn dam, which helped to supply the factory with hydropower.

Anders Beer Wilse, Norsk Folkemuseum

Høie Factories in Mosby in 1922. On the right in the photo is the Sagtjønn dam, which helped to supply the factory with hydropower.

Anders Beer Wilse, Norsk Folkemuseum

The use of hydropower to power mills, grinders, and sawmills dates back several centuries in Sørlandet, the southern coastal region of Norway. In the mid-1800s, many mechanical textile companies were established, several of which used hydropower from rivers and creeks – like the watercourse Høievassdraget, which drains lake Lona. The first spinning mill in the area was established by P. J. Lilloe in 1850, with several other companies following suit. Unfortunately, business was not booming, resulting in many textile companies going bankrupt. In 1882, the textile companies in Høievassdraget were merged into Høie Factories.

Høie Factories was acquired by Oscar Jebsen in 1904 and, under his skilful leadership, the business grew to become one of Scandinavia’s leading textile companies, and one of its largest with several hundred employees. The textile products were regarded as top-class in Europe. After more than 150 years of operation, production was moved abroad in 2007.

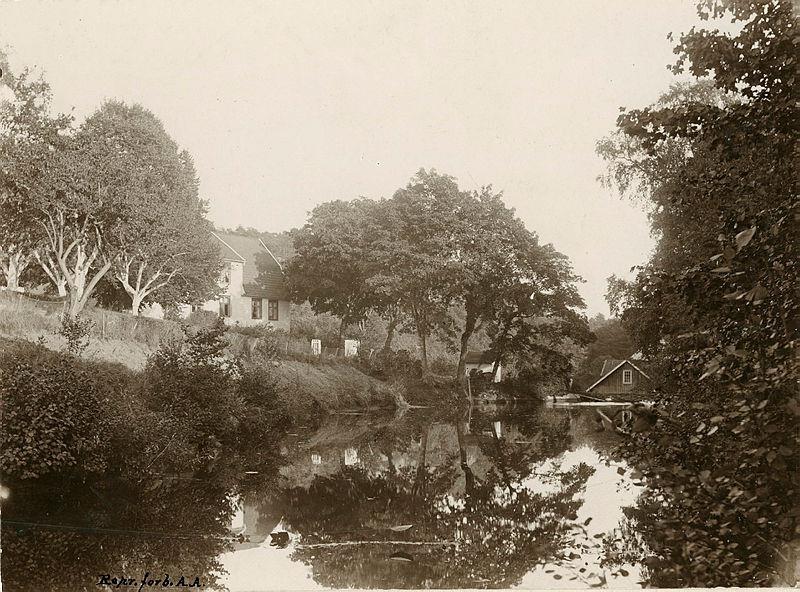

In Jægersberg, industry emerged along the creek, in the form of several dams and mills.

August Abrahamson, Vest-Agder Museum

In Jægersberg, industry emerged along the creek, in the form of several dams and mills.

August Abrahamson, Vest-Agder Museum

Along the creek Prestebekken in Jægersberg in today’s Kristiansand, we find the cradle of Kristiansand’s industrial adventure. This area has been home to grinding mills and sawmills since the 1600–1700s and, subsequently, stamping mills, distilleries, bakeries, weaving mills, etc. were established. There are still traces of the dams and several of the installations; however, the millpond is gone.

The industrial adventure in Jægersberg was started by Niels Winther Luth Jæger (1772–1840) and continued by Danish-born Iver Albrecht Dahm (1784–1862), who took over Jægersberg in 1824. Both were captains, merchants, and industrial entrepreneurs. During the Napoleonic wars, Dahm had been a privateer licensed to raid hostile merchant ships, resulting in time spent in British captivity.

Jæger obtained damming rights with a view to turning the watercourse into an industrial area. It started with two watermills in 1812–1813, soon followed by a paper mill in 1813–14. The paper mill broke him financially, resulting in the forced sale of his businesses in 1824. His successor, proprietor Dahm, helped to establish the «Company for the Promotion of Domestic Industry». This company started a small weaving mill for cotton fabric shortly thereafter, and already in 1845 both Lilloe’s spinning mill and Dahm’s mechanical weaving mill were completed – the latter with 14 weaving looms driven by hydropower!

Best known as a pioneer in the textile business, the industrious merchant Peter Julius Lilloe had interests in several industry projects. In 1845 he established a steam-driven cotton spinning mill by Prestebekken in Jægersberg. Although Lilloe’s spinning mill was steam-driven, it was profitable from the very start and, due to the good quality of its yarn, his business soon received more orders than it could handle. Challenges then piled up. It was generally difficult for industrial entrepreneurs, who were often young, to raise risk capital. There was virtually no Norwegian banking industry to speak of, and the financially strong citizens preferred to invest in secure businesses dealing in shipping and commodity trade.

Water conditions in Jægersberg being a limiting factor, Lilloe moved his business to Høievassdraget in Mosby in 1850, where significantly more water, and thereby more power, was available.

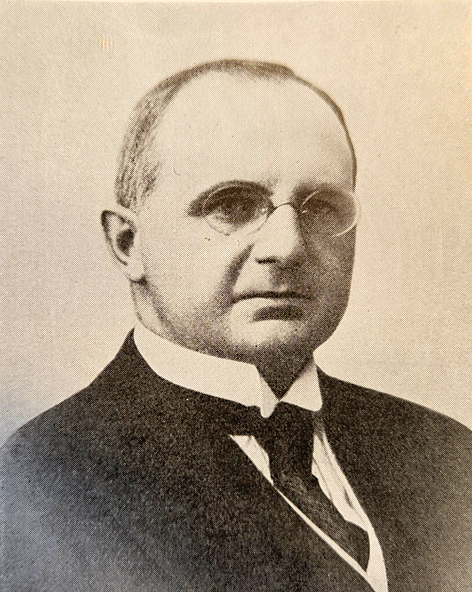

Anders Magnuson (1824–1909)

Bernestvedt and Grieg

Anders Magnuson (1824–1909)

Bernestvedt and Grieg

In 1852, two years after P.J. Lilloe had moved his spinning mill to the Høie waterfall, his British millman Hixton established a small weaving mill in his home on the hill above Lilloe’s spinning mill. Hixton had obtained water rights, but did not get around to switching over to mechanical operation himself. Profitability being poor, he closed down operations already in 1856. Despite his important role in establishing what was to become Høie Factories, we know little about his life and work. The house and weaving mill that he established became known as «Privaten» and were auctioned off in 1856 to the Swedish millman Anders Magnusson (1824–1909), who modernized the weaving mill. With support and incentives from Nydalens Compagnie (formerly Nydalens Bomuldsspinderi [Cotton Spinning Mill]) in Oslo, he rapidly arranged for the construction of a separate weaving mill building, in which he installed 12 mechanical weaving looms driven by a water wheel. The weaving mill burnt in 1872, but was rebuilt the following year with more weaving looms. Following major losses on customers, he was forced to sell in 1882. However, he had other irons in the fire and moved to Kristiansand in 1882 to produce oilskin clothing.

Oscar Jebsen

Unknown

Oscar Jebsen

Unknown

Bergen-born Oscar Jebsen had textile industry in his blood. His father was consul Peter Jebsen, who owned and ran the successful Arne Factories. His mother, Sophia Jebsen, was the daughter of merchant C. Sundt in Bergen, who founded the manufacture firm Sundt & Co. Oscar Jebsen was only 26 years old when he took over Høie in 1904 and was the right man at the right time. Despite his young age, he had accumulated a great deal of knowledge and experience.

After completing practical training at Dale Factories, Jebsen received education at a textile college in Aachen, a city known for its mechanical industry. Here, he also did practical training at both a weaving mill and a weaving loom factory. Later, following training at a hat factory in England, he started a hat manufacturing department at Dale Factories. After a few years as technical leader at Dale Factories, he left for yet another study trip – this time to the USA. Afterwards he worked as general manager at Dale Factories until he purchased Høie Factories. After having made Kristiansand his hometown, he helped to start a number of local industrial companies. Jebsen was also involved in politics and ran a remote farm from 1908 breeding sheep.

The factory’s importance

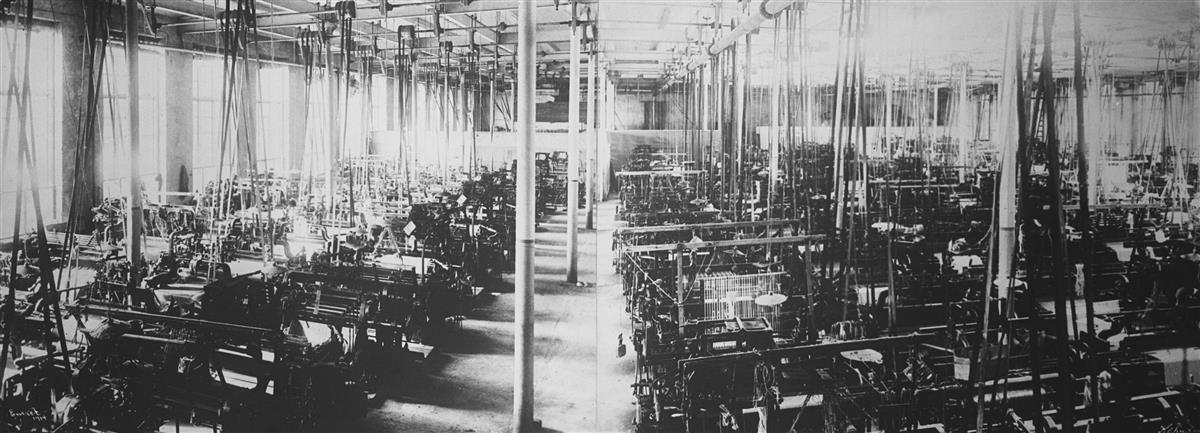

The factory hall at Høie Factories in 1922.

Anders Beer Wilse, Norsk Folkemuseum

The factory hall at Høie Factories in 1922.

Anders Beer Wilse, Norsk Folkemuseum

The factory had a varied workforce divided among several departments. This included weavers, warpers, winders, fabric finishers, dyers, etc., in addition to foremen and officers. Finding skilled workers was difficult. During the 1880s, only half of the workers were recruited locally. Quite a few came from Sunnmøre, while others were recruited in Sweden. Spacious workers’ dwellings were established, and a soup kitchen and lodging were provided for single workers. Other workers rented rooms from the local population, and those who settled permanently at Høie generally found dwellings with a patch of land near the factory.

The management enjoyed showing social involvement. They made much of new hires and subsidized social get-togethers and outings. During World War 2, the company went to greater lengths than most to make sure its workers made it through the difficult times, not least through distributing bonuses and groceries.

Kristiansand’s first car was purchased by Jebsen in 1906. Here he is depicted driving, likely with his wife by his side.

Unknown.

Kristiansand’s first car was purchased by Jebsen in 1906. Here he is depicted driving, likely with his wife by his side.

Unknown.

Mosby and Høie Factories are inextricably linked to national road number 9. In the old days, like today, traffic to and from the Setesdal valley went via Mosby. There was a regular ferry service from Kristiansand and, from there, horse-drawn transport up the valley. Already at the beginning of the 1900s, facilitation of the Setesdalsvegen national road for motor vehicle traffic commenced. After significant improvements in the 1950s, Setesdalsvegen could be classified as a national road in 1965.

It is likely that the well-travelled factory owner and executive officer Oscar Jebsen was well acquainted with cars, not least from his period of study in the USA. In 1906 he returned from Denmark with Sørlandet’s first car. In the next six years, he drove between his home in Kristiansand and the factory in Mosby – to begin with most likely as the only motorist. The small, single-cylinder engine reportedly struggled on the steep stretch up Høiekleivene.

There has been a great deal of discussion concerning the car make, but it was a vehicle from the German car make Hansa-Automobil Gesellschaft m.b.H, or simply «Hansa». However, probably due to hard feelings over Danmark’s defeat in the Danish-German war of 1864, the Danish importer had taken the liberty of removing the manufacturer’s logo and renaming the car make to «Danica», a name that was more acceptable to Danish customers. The Hansa engine was from the French De Dion Buton and, due to its reliability, the vehicle was a preferred car among salesmen and doctors, hence the term «Doctorwagen» in German – a nickname later associated with early Opel models.

Between 1940 and 1942, Høie Factories was an important hub for the Norwegian resistance and the resistance movement Milorg. The factory often served as a reception and distribution centre for resistance material dropped from airplanes at several places in Agder. It was also a place where people who needed to flee from the Germans were hidden at times. The factory’s central role was due to several factors. First, the workers as well as the management at the factory were involved in the resistance struggle, both through active participation and as supporters. Second, the factory’s workers had a great deal of competence in many fields, which was important to the resistance efforts. The third factor was related to the factory’s central location by the Setesdalsvegen road and near the railway. The factory’s cars drove from here to various places throughout the county, enabling them to take material and people with them in relative safety.

Unfortunately, the Milorg network in which the factory was involved was wound up in 1942. Several arrestations were made and many people had to flee.

Post card photo depicting Høie Factories on fire.

Unknown, Oslo City Archives

Post card photo depicting Høie Factories on fire.

Unknown, Oslo City Archives

Høie Factories was prone to fires. In the fire in 1888, three workers distinguished themselves through their extraordinary efforts in extinguishing the fire and received a remuneration of 60 NOK in total from the insurance company. This amount formed the basis of the workers’ health insurance scheme of Høie Factories, which was to prove beneficial to many. In 1906 its members had, for a fixed monthly sum, access to medical services and medicine free of charge, sickness benefits for 60 days, funeral support, etc.

Agder as a hydropower county

Hydropower is an important industry in Agder. The development has gone from mechanical electricity generation, such as mills and saws in rivers, to electric power. Electrification enabled power to be produced in one location and used in another. As a result, electrification of Norwegian society has developed in parallel in urban and rural areas, as opposed to elsewhere in the world where cities were electrified first. This is evident at Høie Factories. When the production of electric energy for use by the factory started in 1902, a power grid was also developed in Mosby. This resulted in citizens there gaining access to electric power much earlier than what was the case in other rural areas in the district. The rest of Kristiansand received electricity in 1900 from the Kringsjå power station in Iveland Municipality. This power station has since been shut down.

Hydropower is still important to Agder, with the county being responsible for 12% of all hydropower produced in Norway. One advantage in Agder is that there is great potential for storing water in reservoirs, which provides for a steady production of electric energy. Consequently, Agder is capable of ensuring stability in energy production while new forms of renewable energy are being developed. Because even though we are responsible for a significant part of Norway’s energy production and have a surplus of electricity, energy needs are expected to increase notably in the future.

Norway is currently Europe’s largest producer of hydropower, and the seventh largest in the world. Currently, over 1,600 hydropower stations are in operation. Several of these can be visited in the Setesdal valley and along national road number 9.

The ruins of the Kringsjå power station.

Theodor Lothe Bruun, Agder Country Council.

The ruins of the Kringsjå power station.

Theodor Lothe Bruun, Agder Country Council.

Established on 1 May 1899, Kristiansands Fossefall & Elektricitetsværk is one of Norway’s oldest power companies. It arranged for the construction of a power station in Iveland Municipality, the Kringsjå power station, which supplied electricity to the citizens of Kristiansand. Production at the power plant was commissioned on 21 November 1900 and the number of subscriptions quickly increased. In 1902 the power company had 651 subscribers.

Kristiansands Fossefall & Elektricitetsværk started as a limited liability company, but was acquired by Kristiansand Municipality in 1914. Today, the company is part of Å Energi. Operations at the Kringsjå power station continued until 1957. Today, the ruins of the power station can be visited as part of the round trip with the Setesdalsbanen vintage railway and the Tømmerrenna timber slide. Departure from Grovane in Vennesla Municipality.

Hiking opportunities near Lona and Høie Factories

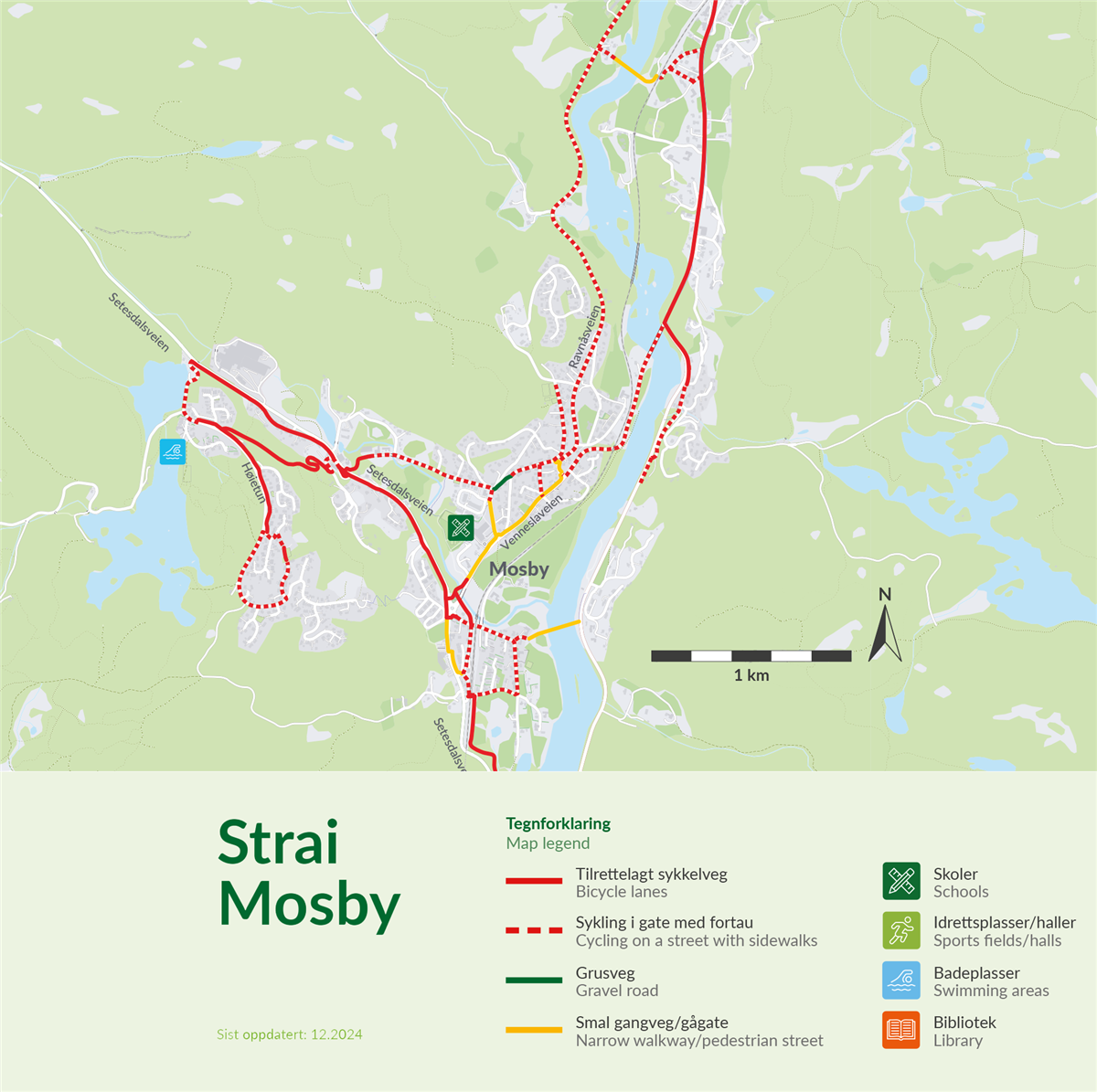

Swimming areas around Mosby. The map is a section of a map from Kristiansand Municipality.

Kristiansand Municipality

Swimming areas around Mosby. The map is a section of a map from Kristiansand Municipality.

Kristiansand Municipality

The old water reservoirs of Høie Factories are no longer used as such, with some having been repurposed. Not far from Høie Factories is Hestvannet, whose dam was built in 1913. A municipal recreational area has been established here, with picnic tables and a pretty beach. We recommend that you park by the factory and walk the remaining distance; see the map above.

From the south side of Lona, it is possible to do a 3.1 km hike to Godheia, an abandoned old farm from about the 1700s. The hike is regarded as relatively easy.

Map from Ut.no (In norwegian)

If the hike to Godheia is a bit short, it is possible to continue on to Hesteheia at Eidså. This is a 4.9 km hike with a total ascent of 233 meters.

At Hesteheia you can experience three generations of cultural monuments. There was allegedly a signal beacon here, which was part of the signalling network along the coast. From each beacon you could see the next beacon. In the event of trouble somewhere in the country and the country’s military force or fleet needing to be assembled, the beacons were lit and an alert signal was sent.

In 1850, a cylindrical survey cairn was built here, and in 1958 a broadcasting mast was erected. The mast is 217.5 meters tall.

Hikingmap from ut.no (In norwegian)

The «brudle» on Bruliheia – this reportedly symbolized a bridal procession over the mountain in times past.

Theodor Lothe Bruun, Agder County Municipality

The «brudle» on Bruliheia – this reportedly symbolized a bridal procession over the mountain in times past.

Theodor Lothe Bruun, Agder County Municipality

On Bruliheia there are several fascinating cultural monuments. Many are associated with one of the most important journeys in many people’s lives – the bridal procession.

From Lona, you hike over Salen to the top of Bruliheia. Here you follow a section of the old Fjellmannsvegen trail which connected the Setesdal valley with the coast before the Setesdalsvegen road was constructed. There are traces suggesting that the road has been in use since about the 400s, if not longer.

The trail traverses the old Brudledheia farm. The farm was in use here over two periods, first from 1719 to 1781 and then from 1877 to the 1920s, as well as during the summers until the 1930s.

At the top of Bruliheia there is a «brudle», a series of stones which, according to tradition, were placed in connection with a wedding. Each stone allegedly represents a person in the bridal procession. There is also a «brudled» at the top of Salen, just southeast of Lona.

Hikingmap from ut.no (In norwegian)